2003 – “Bijoux”

2003,

Exhibitions

Why do I make jewellery?

Bijoux 2000-2003

Galerie Gladys Mougin

Paris

October 16th to December 16th, 2003.

I started making jewellery because I felt our era was lacking in treasures. A treasure is precious because it is unique, but it also holds an enigma, a mystery, a question or a secret that looks back at you, speaks to you, moves you, and longs to be passed on. These jewels are, for me, threads of intimacy between self and self, talismans rather than ornaments.

I am not, strictly speaking, a ‘jeweller’, just as I am not a ‘photographer’ or a ‘sculptor’. People have said my jewellery was sculpture and my sculptures were jewellery. For me, these different forms of artistic expression matter less than the state, the moment they are created.

Travel has long been my first source of inspiration, but when I’m not travelling, I find it in poetry. I jot down phrases like “sky-blue enamel” or “silver spray”; scattered through my reading, I find the words of mentors and these are enough to spark new pieces. I make jewellery with no precedent and if I sense I am repeating myself, I stop.

Fluidity runs through all my work. The sea is my element. I was born under the sign of Pisces. I love lightness. I envy dancers who barely touch the ground and the grace of those who practise tai chi, their movements flowing, precise and serene. I find peace swimming underwater and singing like dolphins. Gazing at the ocean floor delights me. Sometimes it appears as a marvellous garden, where seaweed seems to dance. In life, I love fluidity, drifting currents, sudden associations, quiet correspondences, the words of free-thinkers, and visual collisions.

As a child, I dreamed endlessly and often mistook my desires for reality. As an adult, I kept dreaming, only now I had the means to bring some of those visions to life Songes d’or ou l’origine rêvée gave rise to a series of twenty-three vases that seemed to float in space. It was the visualisation of a dream, expanded across a surface four metres high and eight metres wide.

Erosion, strata, and geology are recurring themes in my work.

Atlantide, my first exhibition, was imagined as a garden of time and memory. Seven gouaches on canvas, each measuring 4.20 by 2.80 metres, traced the contours of an imaginary landscape. From one to the next, there was a slow progression, from liquid to solid. Matisse spoke of “swimming in colour,” and for me, immersing myself in these large formats was a return to the scale of childhood.

In this collection of jewellery, I use stones the way a painter uses watercolours. I achieve subtle gradations with ease because every colour already exists in nature, and I love searching for them there. Making jewellery remains a form of play for me, spontaneous but grounded in a broad base of knowledge. It is a joyful process. Along the way, I meet gemologists, archaeologists, importers of unusual raw materials, and casters. To bring each piece into being, I work with stone-setters, goldsmiths, and pearl threaders, all based near the Place Vendôme in Paris.

My jewellery often takes time to come into being. It evolves in stages and sometimes benefits from happy accidents. One day, while walking in southern Morocco, I picked up an acacia thorn. Its softly rounded shape reminded me of Brancusi’s bird. Later, it found its place in a box filled with objects gathered from a beach in southern Yemen. The sea had shaped them from a single fragment, as in antiquity. They ended up together in a box I labelled Instruments de la Passion, which would later inspire a piece with the same name.

At times, I take liberties with traditional techniques or make unexpected gestures within the world of high jewellery. The Croix Océane is a cross in faceted silver, adorned with sandstone and schist pebbles. It evokes the medieval treasures I so often admire at the Musée de Cluny. I wanted the silver to have the worn, softened finish that salt and seawater bestow over time. In the end, I achieved that effect using a dental drill bit.

Still, outside the usual language of fine jewellery, I sometimes use unexpected materials such as pink mica, used in my piece Asphodèle-rosée. In Trois arbres d’enfant, I used green sea glass pebbles, set in fine gold alongside the greenest of baroque pearls which I attached to a piece of coral, all of these elements come together to evoke the foliage of a tree branch drawn by a child’s hand.

I was encouraged to blend materials, genres, and techniques in this way when I saw, among the Medici treasures in Florence, a cherry stone carved as if it were the most precious diamond.

It takes a light hand and a precise touch to balance matte and shine, shadow and light within a piece of jewellery. I am lucky to live in Paris and to collaborate with extraordinary artisans, each carrying generations of skill in their hands. I give them drawings measured to the millimetre and closely follow each stage of the process. All of my pieces feel as though they exist outside of time and trends, entirely free to preserve their mystery. While I do take pleasure in reconnecting with the elements of nature, what matters most to me is conveying a feeling, reaching someone quietly and deeply.

When I sketch out designs, I sometimes listen to certain pieces of music on repeat, depending on my mood. At the moment, it’s Couperin and Charpentier.

In Paris, I live in an aquarium in the sky. It is a cheerful string of small rooms with an eighteenth-century spirit, like a Lully score, sparsely furnished and filled with light. The costume workshop of the Odéon Theatre is my only neighbour.

I tend to travel against the tide, drawn to cities that nap at midday and to small museums forgotten by tourists. The Mauritshuis in The Hague, the Beyeler Foundation in Basel, the Piraeus museum, the Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, the archaeological museum in Naples, and others like them.

I nourish a passion for the history of photography, for painting and for art in all its forms. The artist who moves me most is Agnes Martin, who comes closest to my idea of perfection.

ANNABELLE D’HUART

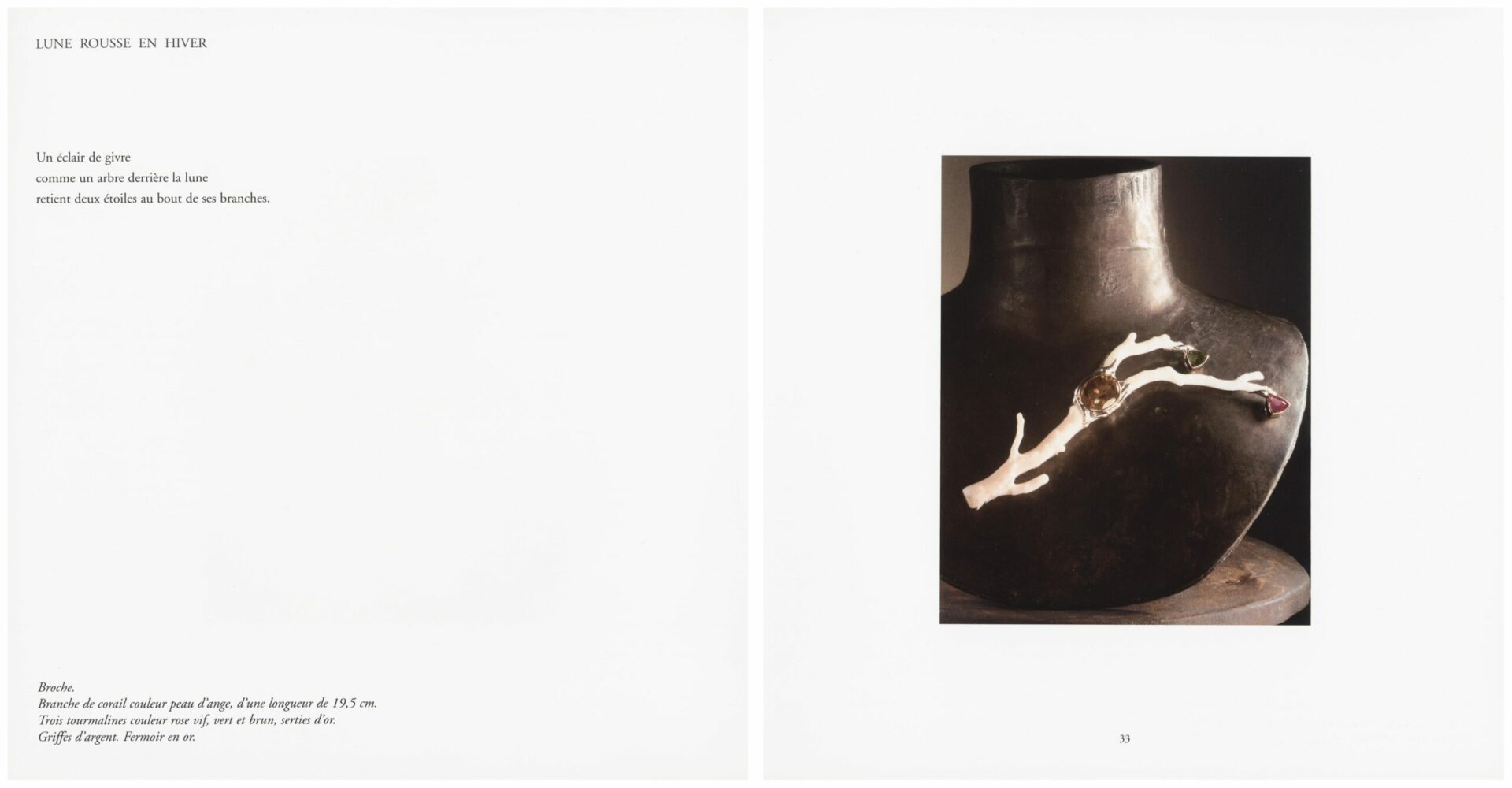

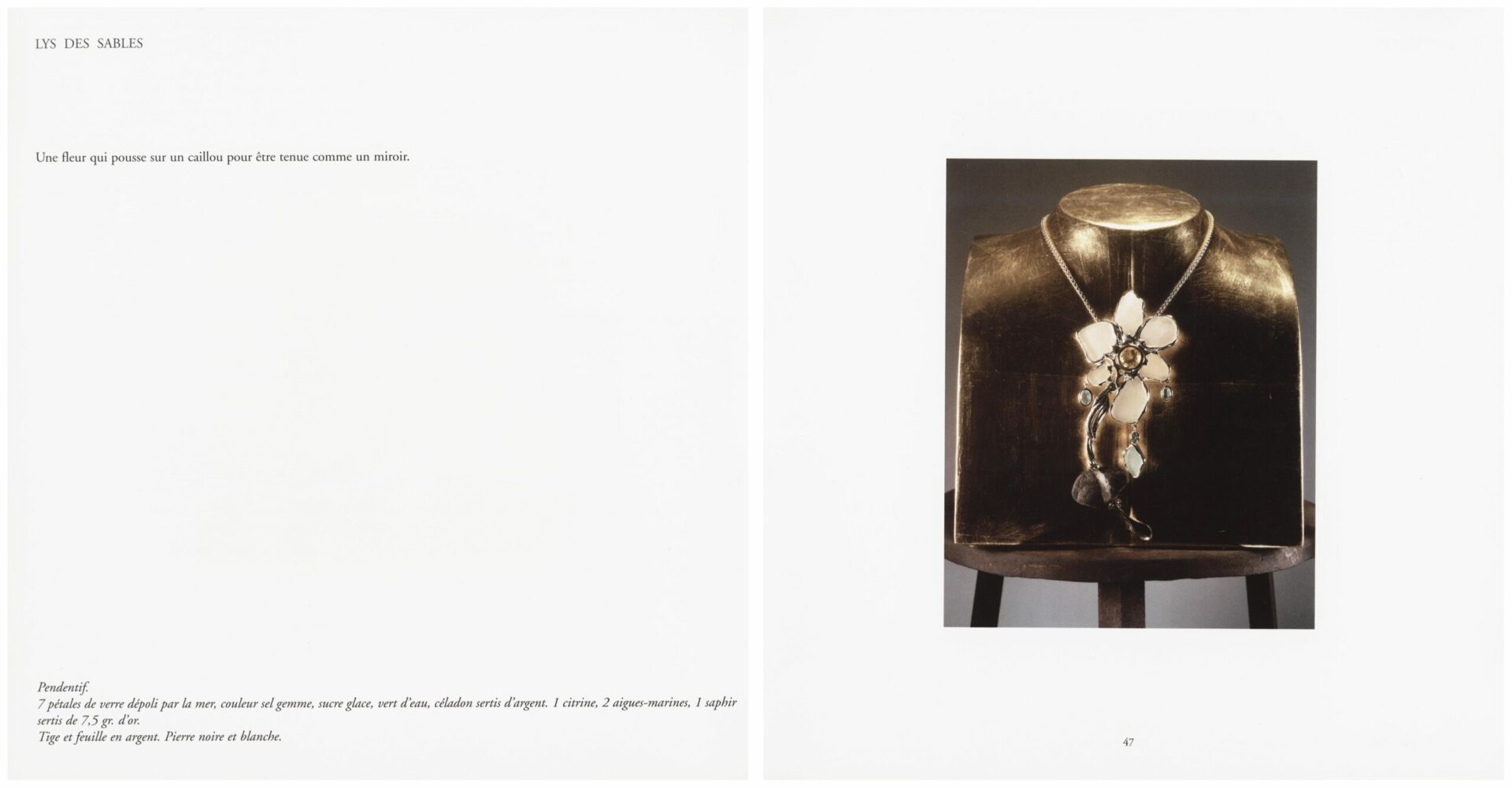

Twenty or so pieces of jewellery. Defying the norms of conventional jewellery making, Annabelle used jewels like watercolour paints, in a way devoid of hierarchy. The result is a series of one-of-a-kind pieces, which combine materials rarely seen together, such as sea glass set in gold. As much art as jewellery, every necklace enjoys a bespoke bronze bust to hang from and each has its own story. They are modern talismans somewhere between adornments and works of art, not ornaments, but rather personal armours. Annabelle worked alongside award- winning writer and poet Marc Cholodenko to create poetic titles, such as Jules Verne’s Fish or the Intoxication of the Depths or The Candy Cane Empress, and tales, sometimes just snippets of tales, for every piece. Their collaboration was made into a limited edition catalogue for her exhibition Bijoux 2003 at Galerie Mougin in Paris.

Location: Gladys Mougin Gallery, Paris.

Painter, sculptor and photographer, known for her monumental installations, Annabelle d’Huart also appropriates the field of art in reduced scale for her jewelry creations. She is demolishing the traditional codes of jewelry making and creating a better way to extract a new vision of the beautiful from her assemblages. Is it because Annabelle d’Huart has traveled the world for a long time—gleaning from her random wanderings, here, a pearl of a strangely green color or a fragment of coral shaped like a winged Samothrace; there, the shell of a tortoise or a piece of stained glass—that her current work on jewelry seems like a quest? This is no “remembrance of things past,” but the search instead for an emotion that is both active and contemplative in the way it comes into contact with objects and forms of life. “I create jewelry toward which you must go to make it a part of yourself. Each of us is responding to a need, to a nature. In a world in which luxury is extremely codified and responds to norms dictated by financial conglomerates, I think its necessary to introduce a bit of mystery,” she explains in a childlike voice, while also confessing having spent years before feeling worthy of the identity of “artist.” And yet! This Parisian, who studied first at the Ecole Camondo and continued with art history in Florence, has never ceased to conceive of her work with that rare independence of mind characteristic of the great creators. Her journey began in New York, where she spent two years photographing American minimalist artists. She then detoured by way of Istanbul to produce a book on harems. She returned to Paris, where her partner of the time, the architect Ricardo Bofill, helped her gain a sensitivity to the tri-dimensional qualities of forms; then she wrote several books, while at the same time directing a research unit on the evolution of materials. In 1990, Annabelle burst into the world of painting with ATLANTIDE, a series of enormous gouaches on the theme of time and memory. With SONGES D’OR OU L’ORIGINE REVÉE, she investigated sculpture through a 4m-x-8m installation, composed of twenty three terracotta vase forms. This piece gave the impression of being suspended in a void. Beginning in 1991with TALISMAN, a “twenty-eight-day necklace” in ebony and solid silver symbolizing the phases of the moon, whose production had been entrusted to her by the Société des Amis du Musée d’Art Moderne (shown since that time by the Guggenheim Museum in New York and acquired by Maison Chanel), her approach to jewelry continues to arise from the same fervor for creation. On busts of bronze—specially conceived by the artist—she placed twenty-eight wonders of creativity and expertise. “Even if they aren’t worn, my jewelry must nevertheless be able to be looked at, and contemplated as a complete work of art.” Each element tells a story. A sort of mini-text whose plot and punctuations are revealed according to the materials that compose them. Precious matter, such as gold, silver, diamonds, sapphires and cultured pearls are used. Semiprecious stones, such as garnets, turquoises, aquamarines, amethysts or topazes; elements mottled by nature, such as pebbles, branches of coral, fragments of quartz or mica, or rosewood. From these heterogeneous assemblages, which are a priori antinomical to jewelry and smithing traditions, an idea of the beautiful, dominated above all by emotion and purity, has come forth. A branch of red coral on an assemblage of white coral, punctuated by gray and gilded pearls, serving as a miniaturized vision of the mythic coral reef of the Pacific. Blue sapphire set with gold in the shape of a fisheye and a luminescent spate of pearls, labradorites, aquamarines and garnets offer a playful interpretation, in the form of a necklace, of the decom Pression vertigo described by Jules Verne. Green pebbles are set with solid gold for a brooch representing a tree, drawn by the hand of a child; a glittering silver cross with pebbles covered in gold cloisonné evoke those sublimes medieval jewels on display at the Musée de Cluny. Twenty-three-carat morganite, encrusted with amethysts, with petals of rose mica set with silver, pink beryl and silver shafts create a necklace in homage to the asphodel or carrot flower. Aquamarine, gold, silver, rosewood and glass pebbles make a necklace referencing “the casting of gold on black water,” in recollection of the paintings of David Hockney. As expressively wrought on the back as on the front, Annabelle d’Huart’s jewelry astonishes and inspires by the discordant blend of influences that permeate it; and all and all, by its manner of serving as reflector of our inner worlds.

PHILIPPE DAYAN